Two Things the Pandemic Didn’t Change About Marketing

Posted on“When someone shows you who they are, believe them the first time” —Maya Angelou

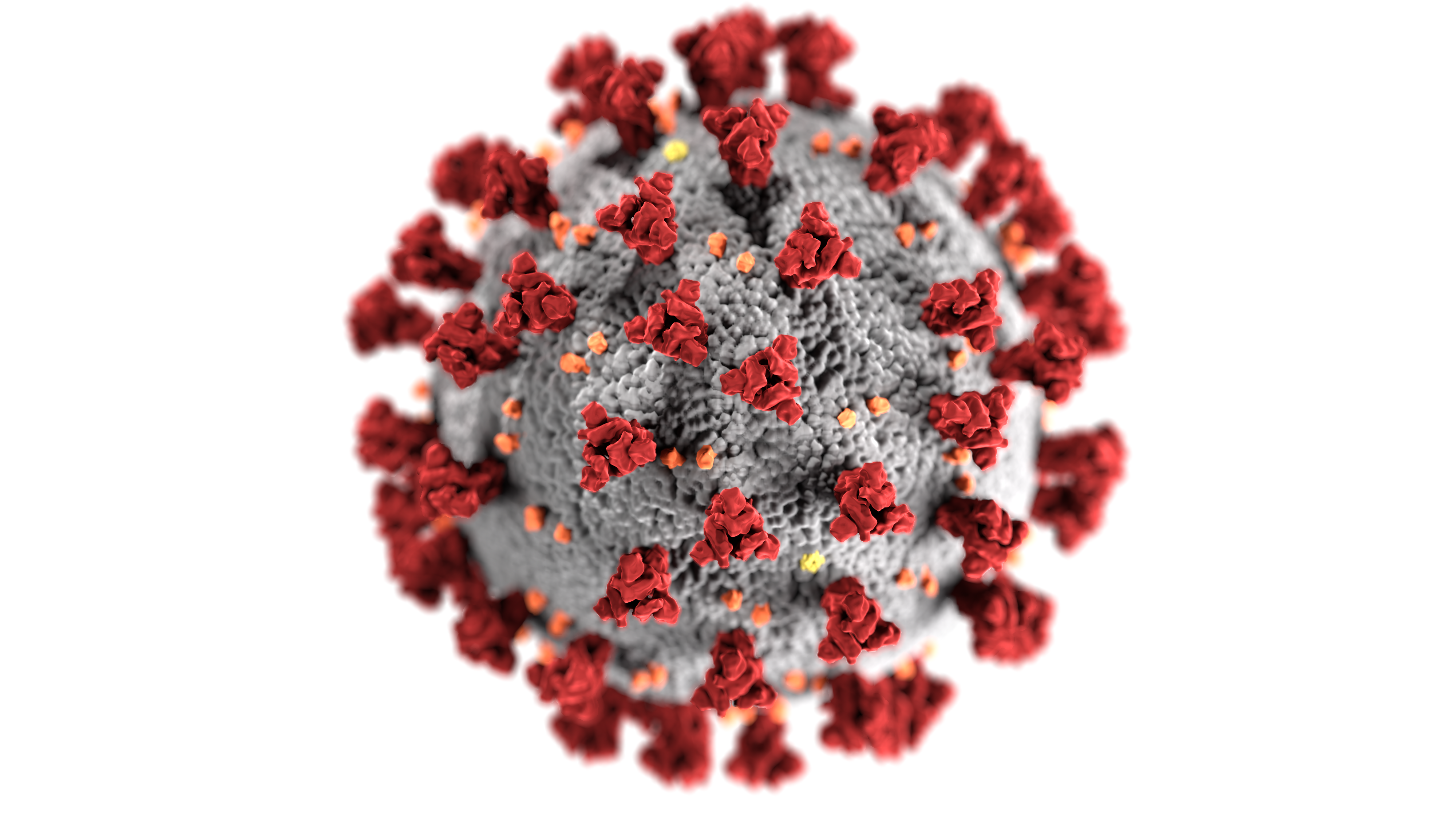

Marketers are confused. They might not be showing it, or even admitting it, but the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has thrown this profession for a bit of a loop. It’s not like marketing stopped, and we forgot how, or we forgot what to do, but a lot of it changed. At some point around the middle of this past March, ads suddenly stopped trying to relate to their target audience and promote a product as part of a particular lifestyle.

Suddenly, every ad sounded the same: “We’re here for you,” they all said. Sometimes it made sense, like when insurance carriers started refunding car insurance premiums to policyholders who were no longer driving every day for their commute. Sometimes, it was a bit of a stretch. I’m not sure how any snack food brand was really “there for me” (emotional eating driven by pandemic-panic aside).

The travel industry took quite a hit in March. People stopped flying, and airlines canceled many flights. People were afraid to stay in hotels, and hotel rooms were largely vacant. So both industries started advertising the special cleaning measures they were taking. Airlines started holding middle seats open and spacing people around the plane (easy to do when the plane is close to empty). And, like other industries, airlines started telling us “we’re here for you.”

Consumers, naturally, found this a bit disingenuous. Yes, I’m going to pick on airlines again. There was a meme circulating on social media that said something like, “You’re there for me? Where were you when my checked bag weighed 51.2 pounds?” Most consumers don’t trust airlines to do what’s best for their customers. We’re pretty sure airlines are going to do what’s best for their bottom line, regardless of how unpleasant it makes our flying experiences. The arrival of a dangerous virus did not change our perception of those brands.

To keep your customers and your brand reputation, you must do these two things, pandemic or no pandemic:

Build Trust

Why? Because they didn’t build trust before. Airlines have behaved in ways that make the flying experience increasingly unpleasant. From cramped seats, to reduced food and drink services, to luggage charges and pretty much anything else, you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone who thinks flying is improving (except, maybe, for those who just reached top status with their airline, but they’re in front of that curtain, not next to you).

And now, even as the pandemic rages on across the US and around the world, some airlines are returning to booking planes to full capacity, making flying a scary proposition even for the hardiest and healthiest travelers. This is exactly the behavior we’ve come to expect: It’s not about doing the right thing for your customers; it’s about doing the best thing for your bottom line. Thus proving our distrust and making all the claims of being “there for us” as disingenuous as we thought they were.

Companies that were successful in “being there for us” during the pandemic were those we perceived as “there for us” before the pandemic, and we will likely think they are “there for us” for some time to come. They’ve made efforts to build a brand we trust, not just because they ask us to, but because they do what is needed for a brand to build trust:

- Speak to us (the target audience) in a way we can understand well how your offering will benefit us.

- Deliver your offering reliably and consistently in a way that meets (or exceeds) the expectation you’ve created.

- Make it easy to resolve any issues or dissatisfaction with any part of your offering.

- Show us that, by doing business with you, we will make the world a little bit better (or at least not make it any worse (by our own standards).

The lesson for companies today: Don’t expect your customers to stick by you and trust you when there’s a crisis, if you have not previously built trust and stuck by them.

Build Relationships

This is a closer relative of building trust, but a relationship is more than just trust. To be honest, I’ve never trusted the airlines, but for all the years I’ve traveled for both business and pleasure, I expected that eventually — if I stuck to one airline — there would be something of a relationship. Even ignoring the great business (and personal) advice that a good relationship is built on trust, I held out hope.

So I remember well, when after years of reaching the top status on one airline, I suddenly stopped flying (I left a job, but I also needed a break from life in the air). I did not fly that airline again for almost a full year. I expected (maybe without any rational basis) that one day I would get an email asking what happened, why I stopped flying or when I might be back (maybe even with a special offer of some kind). It never happened. There was no relationship. It might be one of the reasons I love picking on airlines.

Both consumers and businesses are buying much less, and it’s likely that even in the most necessary of businesses, you are seeing a reduction in revenues. But it’s far from true that anyone has stopped buying altogether. Money is being spent, and while much of how it’s spent is actually determined by necessity, the choice of the company with which to do business is often based on the relationship you’ve had over time. If your relationship with your customer has been good, they are likely to continue to do business with you, or if they can’t right now, return to you when they can. If your relationship was weak or, as in my example above, non-existent, don’t expect them back.

We often hear the mantra that, even in a world driven by quarterly results and immediate gratification, a long-term view — and investments in the long-term — is what will win. I’ve seen it turn out to be true in so many cases (and have seen short-term thinking fail just as often). Trust and relationships don’t come easily, and they take time and persistence to develop. But if you want your business to be the one your customers turn to in a crisis and return to afterward, these are not optional investments.

Make sure your promises, your product and your people are all ready to deliver every day to ensure your customers stick with you through thick and thin.